I’ve been reading a great deal since 2020 began, and while most of what I’ve read has been enjoyable (or I wouldn’t finish), only a few books have hit that high note that makes reading truly exciting. That’s why I had high hopes for Daniel Kehlman’s Tyll. I was not disappointed. Tyll is set during the Thirty Year’s War in central Europe and it ranges widely: from domestic to royal settings; from rural peasant life to circuses and war; and from witchcraft to pseudo-science. All this in under 350 pages: a full canvas of human emotions.

I’ve been reading a great deal since 2020 began, and while most of what I’ve read has been enjoyable (or I wouldn’t finish), only a few books have hit that high note that makes reading truly exciting. That’s why I had high hopes for Daniel Kehlman’s Tyll. I was not disappointed. Tyll is set during the Thirty Year’s War in central Europe and it ranges widely: from domestic to royal settings; from rural peasant life to circuses and war; and from witchcraft to pseudo-science. All this in under 350 pages: a full canvas of human emotions.

Tyll is based on the German folk character Tyll Ulenspiegel (there are various spellings). He’s a joker and trickster with magical powers: a magician and an exposer of human foibles. The original stories about Tyll are set earlier, in the 1300s, but many writers and musicians have made use of this archetypal character ever since. Kehlman’s book is set in the 1600s which allows him to take advantage of the political turmoil of the Thirty Year’s War, a horrifically bloody contest between Catholics and Protestants and a struggle for hegemony among various states.

This was a time when Satan could be blamed for almost anything and frequently was. Tyll grows up in a rural village; when his father is executed by the Jesuits for heretical beliefs, Tyll runs off with a neighboring girl, Nele. They travel from town to town where Tyll’s skills as a tightrope walker bring in spectators and a little cash. Their adventures and misadventures bring them close to danger and put them in the middle of war and politics. There’s a fair amount of satire. It all felt very Brechtian to me–a good thing. There have been many adaptations of the Tyll Ulenspiegel story in all types of media: music (Richard Strauss), films, novels, and comics. You’ll often see the story used in children’s books, but it’s really quite dark and satiric. There’s very little in Kehlman’s version that would be suitable–or understandable–for children.

Characters in folktales are often enigmatic so they provide fertile ground for writers to create character and motivation. For readers, it’s a chance to see a story from a different angle. One of my favorite novels is The Song of Achilles, Madeline Miller’s brilliant retelling of the story of the friendship of Achilles and Patroclus. Margaret Atwood’s novel The Penelopiad reimagines the life of Penelope as she waits for Odysseus to return. And Pat Barker’s The Silence of the Girls, about Briseis, the woman who played a pivotal role in the Trojan War, is also excellent and a great companion piece to The Story of Achilles. And now you know my weakness for literature about the classical era.

I was privileged to know Deirdre Bair, who I met several years ago through my friend Jane Kinney-Denning. I can’t consider myself more than an acquaintance, but it was a delight to know her. She died last week, not from the virus. She was in her eighties, but was working on another project, a book about T.S. Eliot. Deirdre didn’t shy away from complex, difficult topics! She was always kind, elegant, and made you feel like your words were important to her.

I was privileged to know Deirdre Bair, who I met several years ago through my friend Jane Kinney-Denning. I can’t consider myself more than an acquaintance, but it was a delight to know her. She died last week, not from the virus. She was in her eighties, but was working on another project, a book about T.S. Eliot. Deirdre didn’t shy away from complex, difficult topics! She was always kind, elegant, and made you feel like your words were important to her.![Pacific_Sea_Stacks[1]](https://areadersplace.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/pacific_sea_stacks1.jpg?w=195&h=146) If you like to hear stories read, here are some especially good opportunities.

If you like to hear stories read, here are some especially good opportunities. Last Tuesday evening I Zoom-ed into a chat with Roz Chast, the great New Yorker cartoonist and her collaborator, Patty Marx, hosted by the novelist Jean Hanff Korelitz. Roz and Patty were, of course hilarious, even playing their ukuleles briefly for us. Chast and Marx have collaborated on several recent books, including the funny and poignant

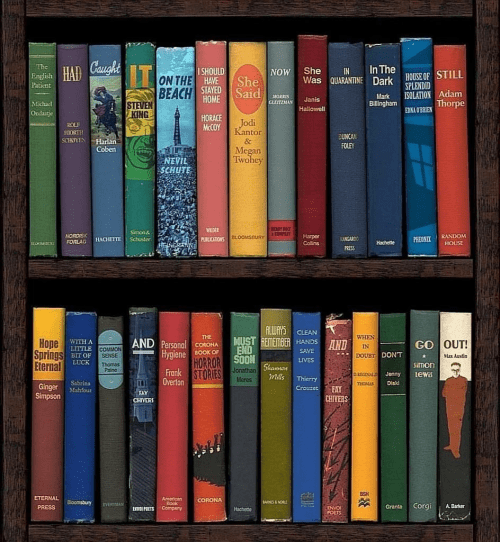

Last Tuesday evening I Zoom-ed into a chat with Roz Chast, the great New Yorker cartoonist and her collaborator, Patty Marx, hosted by the novelist Jean Hanff Korelitz. Roz and Patty were, of course hilarious, even playing their ukuleles briefly for us. Chast and Marx have collaborated on several recent books, including the funny and poignant  Everyone’s posting their list of books to recommend in this strange time, so I thought I’d do it too. I went back over my reading list to find a few books with themes of strength and resilience. Here they are. (They are all available as e-books or e-audiobooks, but I can’t guarantee your library will have them.)

Everyone’s posting their list of books to recommend in this strange time, so I thought I’d do it too. I went back over my reading list to find a few books with themes of strength and resilience. Here they are. (They are all available as e-books or e-audiobooks, but I can’t guarantee your library will have them.)

I read a great essay a few days ago in the Guardian by Margaret Atwood about some of the unusual things she’s doing in this time of isolation. She’s such a witty, clever writer that if she wrote about the proverbial telephone book it would be worth reading. In this essay, titled

I read a great essay a few days ago in the Guardian by Margaret Atwood about some of the unusual things she’s doing in this time of isolation. She’s such a witty, clever writer that if she wrote about the proverbial telephone book it would be worth reading. In this essay, titled  My calendar, which has been pretty empty, is now filling up with these event mice, some of which I quite enjoy so I thought I’d tell you about some of them. I have a reservation for a book discussion this week at

My calendar, which has been pretty empty, is now filling up with these event mice, some of which I quite enjoy so I thought I’d tell you about some of them. I have a reservation for a book discussion this week at  I also signed up for a “writerly chat” this evening between Rebecca Makkai and Jean Hanff Korelitz. Makkai is the author of

I also signed up for a “writerly chat” this evening between Rebecca Makkai and Jean Hanff Korelitz. Makkai is the author of  The Film Society of Lincoln Center is streaming a movie this week that is a delight to watch. It’s called The Booksellers and it’s about the antiquarian book trade. Ho hum, you think. Not at all. It’s a lively and engaging look at the people who are passionate about hunting down, collecting, and selling old and rare books. There’s some history, some of it referencing Book Row, the stretch of Fourth Ave. in New York that housed dozens of antiquarian bookshops from the 1890s to the 1960s. Most of the film consists of interviews with book dealers: how they got into the business, what they love about it, and their thoughts about how it has changed and where it’s going. Fran Lebowitz provides some funny interludes. These collectors are interesting, thoughtful folks; you will probably feel differently about rare books after seeing this film. And, if you haven’t seen the movie Bathtubs Over Broadway, another film about collecting, now is definitely the time to stream it from Netflix.

The Film Society of Lincoln Center is streaming a movie this week that is a delight to watch. It’s called The Booksellers and it’s about the antiquarian book trade. Ho hum, you think. Not at all. It’s a lively and engaging look at the people who are passionate about hunting down, collecting, and selling old and rare books. There’s some history, some of it referencing Book Row, the stretch of Fourth Ave. in New York that housed dozens of antiquarian bookshops from the 1890s to the 1960s. Most of the film consists of interviews with book dealers: how they got into the business, what they love about it, and their thoughts about how it has changed and where it’s going. Fran Lebowitz provides some funny interludes. These collectors are interesting, thoughtful folks; you will probably feel differently about rare books after seeing this film. And, if you haven’t seen the movie Bathtubs Over Broadway, another film about collecting, now is definitely the time to stream it from Netflix. . The reader sees it from the point of view of Cromwell who is thinking about the events that led up to this day: the political intrigue and the trial. Mantel provides a few details about the gruesome event as Cromwell takes it in. In successive chapters she circles back to Anne repeatedly, so the reader has an ever-increasing awareness of the execution’s brutality and its emotional impact. It’s exactly the way it would happen: you take in what you can at the time, then it comes back to haunt you and you see more.

. The reader sees it from the point of view of Cromwell who is thinking about the events that led up to this day: the political intrigue and the trial. Mantel provides a few details about the gruesome event as Cromwell takes it in. In successive chapters she circles back to Anne repeatedly, so the reader has an ever-increasing awareness of the execution’s brutality and its emotional impact. It’s exactly the way it would happen: you take in what you can at the time, then it comes back to haunt you and you see more. In 1848, a small group of women gathered in the Seneca Falls, NY home of Mary M’Clintock. Their goal that Sunday morning was radical: to set in motion a movement to obtain the vote for women. Lucretia Mott and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, who went on to devote their lives to the movement, were among them that day. The women noticed that it was 72 years since the Declaration of Independence was published and they decided to use that document as the template for their own call for suffrage.

In 1848, a small group of women gathered in the Seneca Falls, NY home of Mary M’Clintock. Their goal that Sunday morning was radical: to set in motion a movement to obtain the vote for women. Lucretia Mott and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, who went on to devote their lives to the movement, were among them that day. The women noticed that it was 72 years since the Declaration of Independence was published and they decided to use that document as the template for their own call for suffrage. I know there are writers among the readers of this blog and I keep an eye out for interesting articles about the writing life.

I know there are writers among the readers of this blog and I keep an eye out for interesting articles about the writing life.