Here are three very different novels–maybe something for everyone?

Fagin the Thief by Allison Epstein. I never read Oliver Twist, so I only knew that Fagin was a criminal mastermind, a trainer and taskmaster of thieving children, an anti-Semitic character written by a racist author. So I opened the book, determined that if it didn’t grab me right at the beginning, I’d put it aside. I enjoyed it and I’m glad I read it, but it has completely satisfied my interest in Oliver Twist. (I’m not a big Dickens fan.) Books that are riffs on characters in novels are hard to pull off, but great fun to read when they are successful. Kudos to Allison Epstein for this one; it’s an absorbing tale with lots of atmosphere.

Fagin the Thief by Allison Epstein. I never read Oliver Twist, so I only knew that Fagin was a criminal mastermind, a trainer and taskmaster of thieving children, an anti-Semitic character written by a racist author. So I opened the book, determined that if it didn’t grab me right at the beginning, I’d put it aside. I enjoyed it and I’m glad I read it, but it has completely satisfied my interest in Oliver Twist. (I’m not a big Dickens fan.) Books that are riffs on characters in novels are hard to pull off, but great fun to read when they are successful. Kudos to Allison Epstein for this one; it’s an absorbing tale with lots of atmosphere.

So Far Gone by Jess Walter. This was such fun to read, packed with humor, great characters, and a crackling story about love and loss. Crusty old Rhys Kinnick lives off the grid, preferring his own company to the craziness of the outside world. One day, without warning, his two pre-teen grandchildren show up at his door and the world crashes in on him once more. Their mother– estranged from Rhys since he sucker-punched her husband at Thanksgiving dinner–has gone AWOL and wants Rhys to take charge of the children. Garrulous nine-year-old Asher believes he’s a chess prodigy; Leah is a perceptive, wise-cracking twelve-year-old, an expert at eye-rolling. To avoid their angry father and his right-wing associates, the three take to the road, but here I must stop and let you have the pleasure of reading on. I read Walters’ first novel, Beautiful Ruins and loved it. His books are catnip for fans of Carl Hiaasen’s novels and the novel Norwegian By Night by Sheldon Horowitz. It also reminded me of the movie Oh Brother, Where Art Thou? in the best possible way.

So Far Gone by Jess Walter. This was such fun to read, packed with humor, great characters, and a crackling story about love and loss. Crusty old Rhys Kinnick lives off the grid, preferring his own company to the craziness of the outside world. One day, without warning, his two pre-teen grandchildren show up at his door and the world crashes in on him once more. Their mother– estranged from Rhys since he sucker-punched her husband at Thanksgiving dinner–has gone AWOL and wants Rhys to take charge of the children. Garrulous nine-year-old Asher believes he’s a chess prodigy; Leah is a perceptive, wise-cracking twelve-year-old, an expert at eye-rolling. To avoid their angry father and his right-wing associates, the three take to the road, but here I must stop and let you have the pleasure of reading on. I read Walters’ first novel, Beautiful Ruins and loved it. His books are catnip for fans of Carl Hiaasen’s novels and the novel Norwegian By Night by Sheldon Horowitz. It also reminded me of the movie Oh Brother, Where Art Thou? in the best possible way.

Love is Blind by William Boyd. Boyd is one of the great prose stylists of contemporary British literature. That doesn’t mean that his novels are stuffy, it just means he tells a great, beautifully written story. Years ago, I read his earlier novel, Any Human Heart and loved it; I’ve been waiting for another opportunity to read more of his writing. This new novel is a rich, absorbing tale, set in fin-de-siècle Europe. The main character is Brodie Moncur, a young Scottish piano tuner, talented enough to be just the least bit arrogant. He lands his first job, tuning pianos in Edinburgh, through a favor, moves on to Paris and impresses a piano virtuoso who hires him as his personal piano tuner. When he falls in love with the virtuoso’s lover, Lika, a beautiful seductive singer, his life becomes complicated. Their forbidden passion is more dangerous than Brodie realizes and it sets his life on a different course.

Love is Blind by William Boyd. Boyd is one of the great prose stylists of contemporary British literature. That doesn’t mean that his novels are stuffy, it just means he tells a great, beautifully written story. Years ago, I read his earlier novel, Any Human Heart and loved it; I’ve been waiting for another opportunity to read more of his writing. This new novel is a rich, absorbing tale, set in fin-de-siècle Europe. The main character is Brodie Moncur, a young Scottish piano tuner, talented enough to be just the least bit arrogant. He lands his first job, tuning pianos in Edinburgh, through a favor, moves on to Paris and impresses a piano virtuoso who hires him as his personal piano tuner. When he falls in love with the virtuoso’s lover, Lika, a beautiful seductive singer, his life becomes complicated. Their forbidden passion is more dangerous than Brodie realizes and it sets his life on a different course.

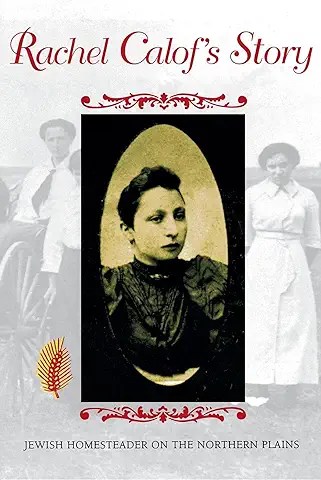

Like many other immigrant groups, Jews took advantage of the US government program that helped settle parts of the Midwest and West by giving a portion of free land to people who agreed to farm it. That’s how Jews came to North Dakota, a frozen, hostile, windswept, and often heartbreaking place to be a pioneer. In 1894, a young Russian woman named Rachel Bella Kahn came to the US to marry, sight unseen, a young man named Abraham Calof, who was living with his family in northeastern North Dakota.

Like many other immigrant groups, Jews took advantage of the US government program that helped settle parts of the Midwest and West by giving a portion of free land to people who agreed to farm it. That’s how Jews came to North Dakota, a frozen, hostile, windswept, and often heartbreaking place to be a pioneer. In 1894, a young Russian woman named Rachel Bella Kahn came to the US to marry, sight unseen, a young man named Abraham Calof, who was living with his family in northeastern North Dakota.